Cursive is dead. Long live cursive.

Just over a year ago, we published an article asking if cursive handwriting is still relevant in today’s educational system. In it, one of the rationales cited was so that students could read historical documents and, as our company’s resident expert in history, that got me thinking about what kind of cursive we actually need.

Just over a year ago, we published an article asking if cursive handwriting is still relevant in today’s educational system. In it, one of the rationales cited was so that students could read historical documents and, as our company’s resident expert in history, that got me thinking about what kind of cursive we actually need.

But first, I think we should have a bit of background. One of the (many) criticisms of the Common Core State Standards is its omission of explicit standards on learning cursive handwriting. In a very real sense, this is representative of us moving away from handwritten communication and the ubiquity of our digital communication tools. Email, text messaging, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube all lack cursive as a necessary part of their use. Cursive is not a significant part of our daily experience any longer. Hand written has become a descriptor for an inferior resume or a quickly scrawled note. At best, it is used to describe an archaic and anachronistic treat received in the mail. Pen-wielding robots are often deployed to fool us into thinking a message was hand written!

Some people see the lack of cursive in the standards as a travesty of the highest order. Tennessee, for example, has adopted additional standards mandating cursive handwriting. Others interpret it as an idea whose time is past due. Hours spent pursuing an archaic form of writing could be better utilized learning how to express ideas more clearly or reading more critically. There is some neuroscience research that shows both children and adults learn language better when writing characters in lieu of typing them. Fair warning, the article is in French, but the gist of it is that in drawing the picture of foreign symbols, both adults and children retain the meaning of those symbols more effectively. So while physical writing is important, this kind of learning is accomplished with printing letters and does not really have anything to do with cursive, despite coming up quite often in the debate.

Neither side is entirely wrong, nor is the debate likely to end soon. In fact, the most compelling reason for me was that historical documents become incomprehensible without a working knowledge of cursive. This is mostly true. However, I would like to propose a radically different idea for solving that problem: Cursive taught as a foreign language. More specifically, like Latin and other dead languages. When learning Latin, as I did in college, effectively no time was spent on learning how to speak the language. This makes eminent sense as, unless you happen to fall into a Doctor Who episode, you aren’t likely to have any ancient Romans to speak with. Even when Latin was a not-quite-dead language, being used as the Lingua Franca of European intellectuals in the Middle Ages, it was largely a matter of written communication. Likewise, as cursive becomes less of a regular mode of producing writing and more of a style of writing that we read in old documents, we should be learning to use it as such.

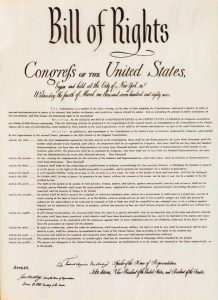

But why are there two squiggly F’s in this one? What is a ſtruggle?

Since the most compelling argument for teaching cursive is so that students can effectively read historical documents, spending years mastering cursive penmanship doesn’t really address the problem of reading historical documents. The style of penmanship of our foundational documents differs markedly from what we teach students in third and fourth grade. Penmanship does even less to introduce the political and intellectual vocabulary of 17th century America. Being able to decipher the Declaration of Independence requires a fairly extensive vocabulary, a solid grounding in 16th and 17th century philosophy, and the ability to decode a script that doesn’t match very well with modern styles of cursive writing. This is exacerbated by idiosyncrasies in spelling, types of print, and handwriting that have fallen out of style. The thorn (when you see a “ye” instead of “the” in old-timey signs), the long s (those weird f-shaped letters where an s should be in old texts, i.e., majeſty), and old ligatures (combined letters like æ that you see in some old texts) are all complicated to read quickly, especially for a modern reader. For American history, the long s is the only real complication, but the other problems remain in British history. Teaching modern cursive writing doesn’t address any of these typographical or vocabulary issues, but all of them at least need to be explained for a novice reader of historical documents.

Since the most compelling argument for teaching cursive is so that students can effectively read historical documents, spending years mastering cursive penmanship doesn’t really address the problem of reading historical documents. The style of penmanship of our foundational documents differs markedly from what we teach students in third and fourth grade. Penmanship does even less to introduce the political and intellectual vocabulary of 17th century America. Being able to decipher the Declaration of Independence requires a fairly extensive vocabulary, a solid grounding in 16th and 17th century philosophy, and the ability to decode a script that doesn’t match very well with modern styles of cursive writing. This is exacerbated by idiosyncrasies in spelling, types of print, and handwriting that have fallen out of style. The thorn (when you see a “ye” instead of “the” in old-timey signs), the long s (those weird f-shaped letters where an s should be in old texts, i.e., majeſty), and old ligatures (combined letters like æ that you see in some old texts) are all complicated to read quickly, especially for a modern reader. For American history, the long s is the only real complication, but the other problems remain in British history. Teaching modern cursive writing doesn’t address any of these typographical or vocabulary issues, but all of them at least need to be explained for a novice reader of historical documents.

So since learning to write cursive does relatively little to help students read historical documents, what should actually be done? The answer is learning to read cursive, of course! It is still (largely) standard English. Vocabulary support and deciphering the characters themselves can be done when it is actually relevant. Most students are first introduced to these documents around 8th grade when they learn about the foundations of our country and our government. That is a perfect opportunity to take a week and start deciphering these weird squiggles. Treat it as another language, which in a certain sense it is, and have students interact with historical documents in their relevant context. It is both sound history education, and still teaches students to read the documents.

Should we still teach cursive?

So is teaching cursive still relevant today? The short answer is not really. That doesn’t mean we should abolish its teaching altogether; however, it is worth reconsidering it as it becomes such a significant time sink in elementary school. We could spend less time teaching cursive penmanship as a skill of declining importance and perhaps free up some time to teach more complex computer skills or go more in-depth into science and history in the elementary years. The real time to address reading historical texts should be when it is relevant. Learning the Constitution could easily be that opportunity. A less intensive approach to cursive that incorporates relevant reading skills might just be the kind of compromise that is most useful.